Justice Blindsided

How does one late morning coffee run begin with a wave while another begins with a pat down? What determines if a used blunt will be dismissed as “kids being kids” or proof that the defendant was a “thug”? Why is one fistfight met with a slap on the wrist while another mere miles away results in expulsion or even arrest?

Lady Justice’s blindfold has often been heralded as a shield against all bias, but what if it has made her blind to the injustices plaguing the criminal justice system right under her nose?

Countless studies spanning dozens of years and thousands of miles seem to confirm this hypothesis. There is a gaping racial disparity in search, arrest and conviction rates between white people and people of color, a disparity that many suggest is much more so a product of prejudicial policies and policing than of any sort of differential offending.

The Precedent

Racism has deep roots in the history of the American criminal justice system. Almost immediately after the Civil War, white Southerners began searching for ways to reaffirm the racial hierarchy they had established under slavery and quickly turned to the criminal justice system. As explained by the Equal Justice Initiative, Black Codes instituted during the Reconstruction Era were used to imprison African Americans for “offenses” as baseless as loitering or failing to show proof of employment. These offending men, women and children could then be leased by Southern state governments to private companies, where they were forced to work unpaid under extreme conditions through the convict lease system, which operated up until the 1930s.

As time went on, government policies became less overtly racist, but inequitable practices were still perpetuated by efforts such as Lyndon B. Johnson’s “War on Crime” program. According to Time Magazine, during this period, police presence, militarization and surveillance increased exponentially in communities of color, pushing disproportionate numbers of African Americans into the criminal justice system.

The Present

Racial discrimination and inequality still permeate through the modern criminal justice system in the U.S., as evidenced by a large body of research analyzing self-reported rates of offending, traffic stop data and arrest rates.

Many criminal justice reform activists argue that this inequity is present from the moment that citizens of color interact with the police. For example, despite nearly equal hit rates, or the percentage of those searched who are found with contraband, the 2019 Illinois Traffic and Pedestrian Stop Study found that in the state, African American pedestrians were 21.6 times more likely to be stopped by police than white pedestrians, and Latinx pedestrians were 6.3 times more likely to be stopped.

A 2016 report from the Chicago Police Accountability Task Force found that “black and Hispanic drivers were searched approximately four times as often as white drivers, yet CPD’s own data show that contraband was found on white drivers twice as often as black and Hispanic drivers.”

While some critics of racial profiling claims argue that these differences are mainly the result of increased police presence in communities of color, a study from Stanford examining millions of traffic stops revealed that African American drivers were less likely to be stopped by police at night when their race was presumably concealed by a “veil of darkness.”

Lake County State’s Attorney Eric Reinhart connected both of these hypotheses to broader issues in the criminal justice system, arguing that “I think it is easier to get away with things when you’re not being racially profiled for traffic offenses […] so racial profiling itself, and I think policing Black and Brown communities harder, begins to lead to the disparities down the road as well.”

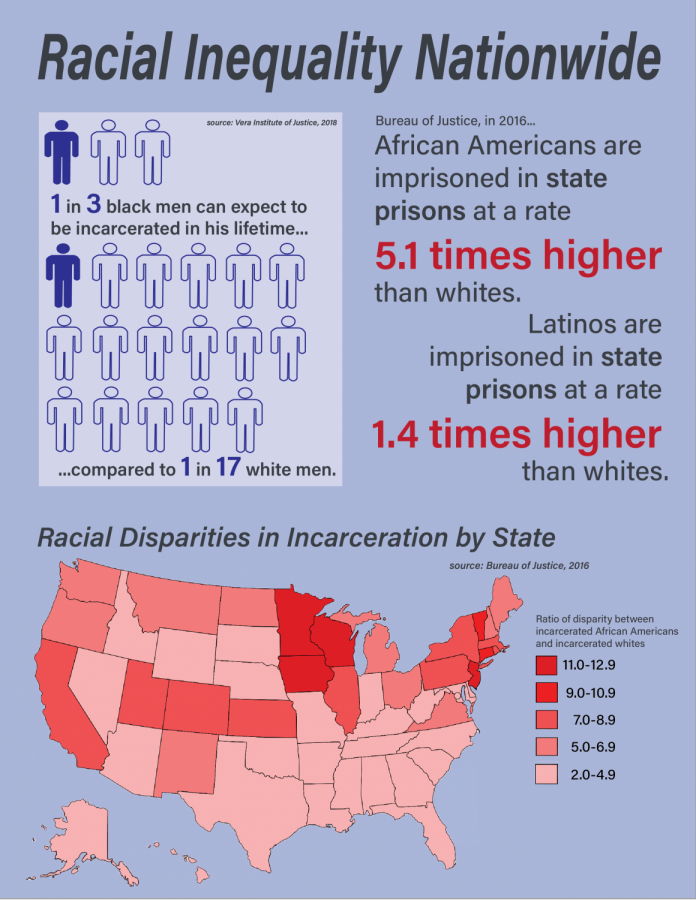

And the disparities are undeniable. In 2016, the Sentencing Project reported that African Americans are incarcerated at 5.1 times the rate of white people and that Latinx people are incarcerated at 1.4 times the rate of white people. Some researchers propose a part of this disparity can be explained by differential rates in offending for certain crimes due to a greater number of African Americans and Latinx people being entrapped in cycles of systemic poverty. However, these rates alone can’t even begin to account for the overrepresentation of people of color in the U.S. prison system.

For example, “The War on Drugs”, a series of policies employed since the 1970’s, has resulted in millions of arrests and has devastated communities of color much more so than their white counterparts. Despite near identical rates of drug usage, an article from the HuffPost concluded that African Americans were more than three times as likely as white people to be arrested for drug possession.

Discrimination extends into the courtroom as well. In a brief on the disparate treatment of African Americans in the criminal justice system, the Vera Institute of Justice cited a 2017 study that discovered “white people were nearly 75 percent more likely than black people to see all misdemeanor charges carrying a potential sentence of incarceration dropped, dismissed, or amended to lesser charges.”

The Young

The criminal justice system can feel worlds away for many high schoolers, but 48,000 adolescents are currently incarcerated in the U.S., according to the Prison Policy Initiative, and thousands of others are forced to confront the threat of being swept up into the system on a daily basis.

The racial disparity frequently observed in the adult U.S. prison population holds for the juvenile justice system as well, and data from the 2019 National Youth Risk Behavior Survey illuminates how these discrepancies may be the product of institutionalized racism or racial bias.

For example, about one third of African American high school students and one fifth of white high school students reported participating in a physical fight in a 12-month period, yet African American youth were three times as likely as white youth to be arrested for simple assault. Additionally, white students were more likely to report carrying a weapon in a one-month period and roughly as likely to report using drugs as African American students, but African American youth were arrested at 3.6 times the rate of white youth for weapons violations and 1.4 times the rate of white youth for drug abuse violations.

Reinhart provided insight on how these disparities arise on a case by case level: “What you begin to see is that young people of color instead of getting a dismissal maybe when they were 18 or 19, they might get a conviction. Whereas maybe people with more access to wealth might get a different type of sentence, and so [there] begins a sort of ladder process” that results in a disproportionate number of youth of color being incarcerated later in life.

The Schools

There has also been a growing emphasis placed on the possible role of schools in funneling youth into the juvenile justice system. In the wake of the first wave of school shootings and perceived increases in crime rates, many schools instituted harsher disciplinary policies that have led to far higher rates of suspension, expulsion, and student contact with police.

The disproportionate impact of these policies on students of color begins as early as preschool where African American students make up 18% of all preschoolers enrolled but nearly half of all preschoolers who served an out-of-school suspension in 2014, according to NPR.

LHS Equity Coordinator Ms. Singleton described why African American students are punished more harshly for behaviors comparable to their white peers, stating that “a lot of times what happens is the teacher’s implicit bias kicks in, and they see a child of color as older than they are and as being more threatening.”

This implicit bias may explain why a 2011 report from the National Education Policy Center found that African American students were more likely to be sent to the office even after controlling for teacher ratings of student misbehavior. The same report also revealed that African American students are more likely to be referred, and by extension, suspended for more subjective offenses such as disrespect, threatening behavior, loitering and public displays of affection while white students are more likely to be referred for more documentable offenses such as smoking, vandalism and obscene language.

While some activists decry the presence of school resource officers in high schools, LHS School Resource Officer Kincaid suggested the increased presence of SRO’s nationwide “has made it less [likely] that kids will go to prison or they’ll stay out of the system longer” because SRO’s can provide counseling and work through the adjudication process to give students who might otherwise be pushed into the criminal justice system a second chance.

The Aftermath

Former President George W. Bush once said, “America is the land of second chance — and when the gates of the prison open, the path should lead to a better life.” However, American society’s current treatment of recently released prisoners and even of suspended students too often deemed “troublemakers” is a far cry from a second chance.

Students who are suspended or expelled even for minor infractions have long been documented at being at an increased risk of performing poorly academically, dropping out of high school and being incarcerated later in life. A recent study from Harvard suggests that even attending a school with high suspension rates reduces one’s chance of attending a four year college and increases one’s chance of being arrested later in life.

After incarceration, even if one was arrested for a non-violent offense, there are multiple barriers that prevent a smooth social and economic re-introduction to the world, especially for people of color.

Officer Kincaid illustrated the multitude of consequences of juvenile incarceration, explaining, “If you get in trouble with the law as a juvenile, it could mean you’re not able to get into a good college or go to college or get financing for college.”

Similarly, the unemployment rate of those formerly incarcerated is much higher than that of the general population, and the New York Times reported that “white men with prison records receive far more offers for entry-level jobs in New York City than black men with identical records, and are offered jobs just as often — if not more so — than black men who have never been arrested.”

Additionally, many recently released people often have less access to health care and mental health services, a particularly troubling fact considering that the National Center for Biotechnology Information found that those incarcerated often suffer from mental illnesses at higher rates than the national population.

The Hope

While the current state of the criminal justice system may be bleak, many in the Libertyville community and beyond are taking important steps to both dismantle the school to prison pipeline and reduce the racial disparities in the criminal justice system.

State’s Attorney Reinhart emphasized the importance of data transparency in generating awareness surrounding racial disparities in the criminal justice system. He also expressed hope that the local school to prison pipeline could be disrupted by introducing community ambassadors to help connect students with the resources they need and facilitate a better relationship between students and those charged with protecting them.

Mrs. Singleton highlighted the potential of restorative justice in both reducing suspension rates and bettering students’ overall mental health because it takes the approach of, “Let’s take a look and see what happened, what caused that behavior… [and] what can we do together to help you and to move past this and just support you” instead of moving to immediately punish a student.

![For the final piece, a combination of Symphony Orchestra and Wind Ensemble played an extravagant song by Paul Hindemist. Flute soloist Dakota Olson had her moment highlighted within this song. “[My solo] was definitely challenging but it was fun too,” Olson said.](https://www.lhsdoi.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/amy-and-joey-shot-600x400.jpg)

Melissa Rieder • Feb 18, 2021 at 2:11 pm

Bravo! This is excellent content.