Embracing my Asian culture in Libertyville

The contrast between my demographic environment in New Jersey and Libertyville opened my eyes to what it means to be Asian American.

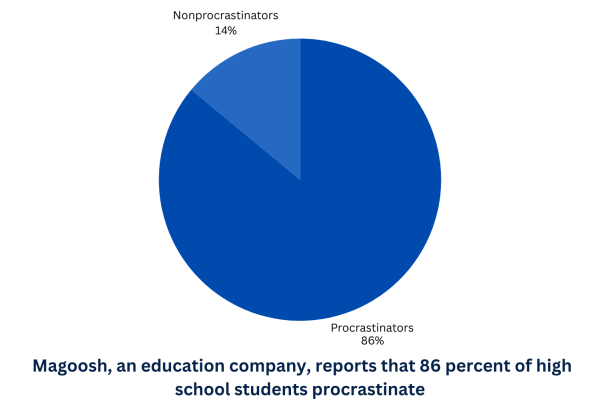

I moved here, to Libertyville, in the summer of 2019 from West Windsor, New Jersey. It was a momentous change in my life, of course, but I was excited. I was enthusiastic about starting fresh, meeting new people and starting high school at LHS. I had no aversions towards moving here except for one thing: the fact that, according to World Population Review, 90 percent of the population of Libertyville is white.

Demographically speaking, West Windsor is an interesting exception to most towns in the United States. Only 45% of the population is white. There are actually more Asians, who make up 47% of the overall population. This is a very stark contrast to Libertyville, which consists of a whopping 6% of Asian people.

In New Jersey, I was immersed in Asian culture and interactions. I participated in Japanese school on Sundays. My dinners every day varied from bukkake udon (a cold noodle dish) to mapo tofu (a spicy tofu and beef dish). Onigiri (rice balls) was my favorite snack to eat at all of my swim meets. My mom spoke Japanese to me. I took Chinese starting in sixth grade at school. I celebrated Asian holidays, like the moon festival, and ate traditional Japanese food on New Year’s Day. These influential aspects of my life sculpted my identity as an Asian American.

However, the most significant feature of living in West Windsor was that I was surrounded by people I identified with. Many of my friends were immigrants. Or they had parents who were immigrants from Asian countries, like me. They were bilingual, like me. They were encompassed by Asian influences, like me. They understood the nuances and complexities regarding our Asian American experiences. I was comfortable being myself around them. I blended right in. It took no effort to find these friends of mine.

When I told all my friends that I was moving to a town in the Midwest, their immediate assumption was that I would be “whitewashed,” a term that describes a minority who has assimilated into Western culture. Many of my friends said things like “I’ll make sure to [put] the Asian back in you when we meet again” and “You better not come back as a white girl.” Thus, even before I moved, there was already an expectation placed on me that I would lose the Asian aspect of my identity.

For a while, I believed that too. I thought that I would have to change to fit in here at Libertyville. I was scared that being an Asian living in a predominantly white community would isolate me from others. I couldn’t change my appearance or name, but I could change how I presented myself.

So I found myself filtering my interactions here. I was careful about what I shared or didn’t share about Asian culture. I attempted to stifle my Asian-ness in an effort to fit in. However, I still felt alienated. I was unable to truly identify with the few Asian peers I interacted with.

Many aspects of my life remained the same, such as the food I ate and speaking Japanese at home. I still loved being Asian. I just couldn’t share it with others.

But as time passed, I started to find myself actively seeking out other ways to be exposed to Asian culture. I never did this in New Jersey. I started researching for places where I could volunteer and practice speaking Japanese. I started watching more Japanese and Chinese shows. I joined my friends in creating an online magazine highlighting the Asian American experience. I became more interested in learning how to make the meals my parents made every day. I put in the effort to engage with Asian culture that I had never put in before.

I had inadvertently started to embrace my Asian heritage at a whole new level. It took me moving to a predominantly white community to truly decide how I wanted Asian culture to impact my life.

Sticking out is part of being an Asian American. I am always going to look Asian, and I am always going to be Asian. I am always going to stand out here. It’s never going to be normal to eat the food I eat. It’s never going to be normal to speak the languages I speak. It’s never going to be normal to participate in the holidays I participate in. However, the fact that it isn’t normal is the very reason why it should be celebrated.

I shouldn’t try to hide the fact that I was brought up as bilingual. I shouldn’t try to hide the rich culture that has filled my past with cherished memories. I shouldn’t try to hide my unique perspective.

In the end, moving here has strengthened my sense of identity. In New Jersey, I was always comfortable being Asian-American, yet I never completely appreciated it. I was in a bubble that had to be broken. Here, I was forced into defining what being an Asian American meant for myself, and that changed me for the better.