Freedom of the Press: How High Schools are Limited

Freedom of the press is a sentiment that rings true throughout the United States’ history, given its place in the Bill of Rights, although freedom of the press in 2018 differs perhaps from the Founding Fathers’ vision.

While the First Amendment to the United States Constitution grants freedom of speech to the people and the press, the rights of certain student journalists across the nation are limited due mainly to prior court rulings that permit some forms of censorship.

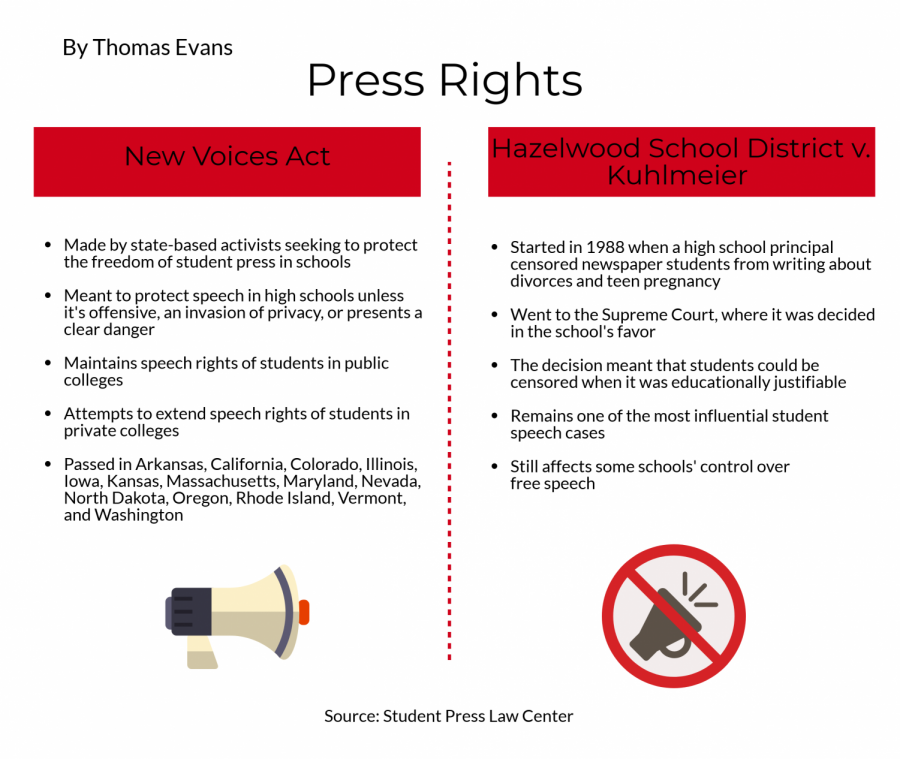

In 1988, the principal of Hazelwood East High School near St. Louis, Missouri, censored that high school’s publication for stories about teen pregnancy and how divorce affects teens. The students on staff questioned the decision, but the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri stated the students’ First Amendments rights had not been violated.

The Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the district court’s decision, and the Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier case then went to the Supreme Court; there, it was ruled that administrators could censor student newspapers if there was reasonable educational justification.

This phrasing includes, in many cases, issues relating to privacy, vulgar language, topics deemed harmful, and overall any situation where a school’s administration believes the publication will cause a significant disruption in school.

According to the Student Press Law Center, an organization that offers legal information regarding law, education, and journalism, the Hazelwood ruling does give more control to principals and administrators, potentially giving them the final say over student publications.

In response to the Hazelwood case, a student-powered legislative movement called New Voices calls for anti-censorship laws and rights for student journalists, with some referring to this legislation as the “anti-Hazelwood law.”

There are two sections of student journalism that the New Voices legislation aims to protect: high schools and colleges. However, New Voices is established in only 14 of the 50 states: Illinois, California, Colorado, Arkansas, Iowa, Kansas, Maryland, Massachusetts, Nevada, North Dakota, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Washington. In Illinois, the New Voices legislation was passed in 2016 for high schools and public colleges.

The balance between the still-existent Hazelwood ruling and the New Voices Act puts pressure on administrators to make decisions about what is best for their students.

“The courts have given principals the right to edit or censor student newspaper stories based on if it’s going to cause a significant disruption in the school, [but] that’s not a clear line, and it’s not a line that I enjoy interpret[ing],” expressed principal Dr. Tom Koulentes.

If a situation arose where harm occurred or is predicted to occur due to the student publication, Dr. Koulentes said he has the responsibility of stepping in. “I want to respect student First Amendment rights, [but] on the other hand, as a principal, I’m held accountable to making sure that all the rules and laws around schools are enforced,” he said.

While he encourages student expression, he also wants Drops of Ink, as well as all publications, to recognize their immense responsibility to their audience.

“[Regarding] a student publication or a professional publication, if it doesn’t do its due diligence in researching a story and attempting to eliminate bias, or at least identify bias in the story, [it] could potentially do damage by creating or shaping opinions based on a limited presentation of facts,” stated Dr. Koulentes.

Dr. Koulentes stressed the prevalence of journalism and its nature of spreading relevant information.

“Journalism has the power to shed light on important issues that people may not want to be public knowledge,” he asserted.

When it comes to discussing important topics in high school publications, communication seems to be especially crucial, even in states where New Voice legislation applies.

“It’s not enough just to have the legislation. It’s also important to continue to talk and have good communication between the groups involved,” stated Dr. Sally Renaud, the executive director of the Illinois Journalism Education Association in a phone interview.

Dr. Renaud stressed the importance of steady conversation not only between the publication staff and administration but also with the publication’s audience. For Drops of Ink, this is the student body.

“Once you have that reputation for doing things well, for talking to your audience and talking to people ahead of time, getting them involved in the process… it [becomes] part of the culture of doing good journalism,” she expressed.

Part of doing quality journalism also includes balancing the role of highlighting truths with doing no harm to others.

As Dr. Koulentes expressed, “What would be the potential damage or harm that could be done if we’re not thoughtful? And how, to every extent possible, do we unearth those things and talk about it so that we at least can’t be accused of doing something thoughtlessly.”

The institution of New Voices in Illinois enables high school journalists to use their freedom of speech in school newspapers to spread knowledge and information with a lesser chance of censorship, although the Hazelwood guideline still affects all states. In states without New Voices legislation, principals are legally permitted to ban topics, often ones they consider too heavy or controversial, such as stories about drug use, the LGBTQ community and sexual assault.

For example, in 2017, the student publication at Evanston Township High School published a spread about marijuana use among teens.

The school’s administration initially ordered papers to stop being distributed and for the online version of the story to be removed.

The paper cited Illinois’s Speech Rights of Student Journalists Act under the New Voices initiative in their defense, which states a school administration must provide justification before censoring. The publication argued they did not promote or encourage marijuana use and therefore didn’t need to be censored.

As a compromise, a revised version of the spread was sent to the principal, with legal and health warnings about marijuana. Though the adjustments were agreed upon, the staff insisted the administration did not have the right to force them to change the spread.

The nature of journalism can present conflicting values in a high school context.

“We have a value of [Drops of Ink] writing about important, real-world stories, [and] we also have a value that [Drops of Ink shares] of protecting students from harm,” said Dr. Koulentes. “The thing that people are worried about is the impact of [a] story on individuals or on groups of students at school.”

Establishing a relationship of trust between all groups affected by high school journalism — the newspaper staff, administrators and the student body — can help to create an environment where information is spread and received reliably, with learning occurring on all sides.

“[There] has to be continuous education and genuine conversation with respect to one another and genuine listening,” emphasized Dr. Renaud. “[That] doesn’t mean you back down, but you listen respectfully and you figure out ways to navigate or find a resolution to whatever that conflict is, and just keep on working on educating.”