The gifted effect

Although it has been previously disputed, evidence has recently shown that gifted children inherit their advanced learning abilities from birth.

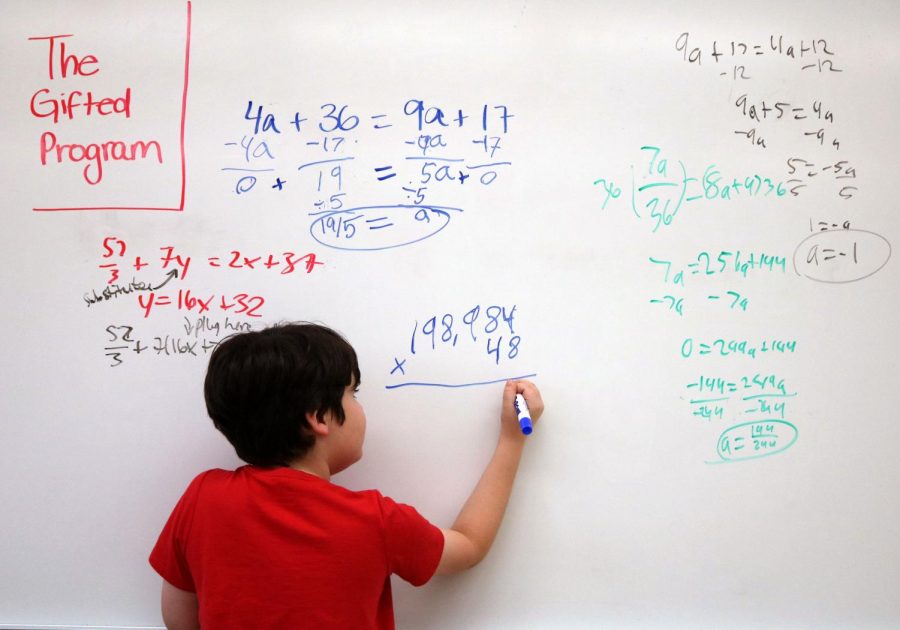

In a small, active classroom with an average of 10 to 12 students is the gifted program: an organized curriculum for academically advanced children who are previously tested to take the separate accelerated classes. After years of often private and secluded classrooms, the effects of such a gifted program are felt through a wide range of impacts, and as students and faculty alike have noted, those impacts are both beneficial and burdening.

The main gifted program that feeds into Libertyville High School is through Libertyville School District 70. The students featured in this story were all involved in the various gifted programs offered through District 70: those being the transfer program to Adler as well as the option to take separate classes offered at the elementary school the students originally attend. Students in either of these programs then continued onto the gifted program at Highland Middle School, which has a program of separated, higher-level classes for English and Mathematics.

While accelerated-style classes were available to students as early as second grade, the established gifted program was offered to District 70 students entering the fourth grade.

Sophomore Izzy Greenberg explained the prerequisites required for being accepted into the gifted program: “[The first round involved District 70 establishing] this list of [student] names from the entire district. The second round of testing [involved the students testing at Adler], and it was mathematics, like visualizing things. [The teachers] would give you these cubes that had different patterns…and you were given a picture and you had to replicate that picture using all of these cubes.”

As Greenberg explained, she joined the Adler Park School’s gifted program in fourth grade and was taught through fifth grade in the same classroom with roughly the same eight children.

“[The switch to gifted classes] was a very different environment because in fourth and fifth grade, it was just this small class for every subject and you’re kind of isolated from everyone else, but it was okay for me because it allowed [me] to accelerate [my] learning in a way that before in elementary school, [I wasn’t] able to,” Greenberg said.

The interviewed gifted students expressed how influential their elementary school teachers were in their early education; one of Adler’s gifted teachers, Mrs. Emily Weber (formerly Ms. Maki), was notably adored among them. The Drops of Ink staff contacted Mrs. Weber, as well as other District 70 gifted teachers, to discuss their teaching experiences within the gifted program for this story, however the District 70 public relations facilitator indicated that the district declined to participate in commenting on the topic.

Mrs. Weber, who taught the fourth-grade gifted academics, was the teacher the students most fondly spoke of. As both junior Matt Wagner and Greenberg individually stated, Weber’s engagement with technology and her care for the children helped create an environment of positive learning.

“[Mrs. Weber] was amazing. She was super tech-oriented, so we had iPods in the classroom and we got to use those a lot,” said Wagner. “That’s what got me interested in technology because just seeing how you can use [iPods] for things aside from just games, like [using] them in an educational way, was super cool.”

Ms. Marissa Frederick, a school psychologist at Libertyville High School, explained how a rigorous, gifted education can be quite positive: “[The gifted program] sets [students] on this high-achieving path, and they start working hard at a really young age, which sets the tone for the rest of [the students’] education.”

However, some of the students interviewed had negative experiences pertaining to the gifted program as well, the most prominent being the stigma of the word “gifted” itself.

Becca Lothspeich, who graduated LHS in 2015, expressed how she struggled with fulfilling the expectations of the term “gifted.” In her elementary years in the program, Lothspeich explained she often dealt with teachers and fellow students who expected her to understand the challenging schoolwork taught in the program and would scold her when she could not meet their expectations.

“I remember not knowing the answer to some things, and [the teacher would] belittle me, and make me feel so dumb, so stupid, for not knowing this,” explained Lothspeich, over the phone. “Part of the negative experiences with the gifted program [are] the expectations that are set on you…[people] just expected us to have this inherently gifted [knowledge].”

The other students interviewed each individually expressed a similar concern and the pressure that comes from those expectations can be detrimental. Ms. Frederick said the pressure behind the word “gifted” can affect both students inside and outside the program.

“I think that when [students] are called ‘gifted’, then [if] they encounter a problem, or a difficulty that might not be something that they encounter regularly, [they] don’t have the emotional wherewithal to be able to manage themselves, or [if they] don’t have support in place to help themselves in those situations, it can be really upsetting to get a problem wrong. I think it’s a lot about perception [as well],” she explained.

As junior Alex Houser communicated, the pressure on her became overwhelming: “[At Highland Middle School], I did sixth and seventh grade [gifted Language Arts] and math, but I dropped [the gifted program] because it was just way too much….It was a lot of pressure, I think. That was the biggest thing, it was more pressure to have really great grades, and pressure to get A’s and also to do well in my other classes. And I guess, I was 14, and I [wanted] to enjoy middle school because I was always so stressed.”

Those interviewed expressed that, while rigorous academics are positive for their education, the staff in charge of any kind of gifted program must help provide a healthy balance for students, academically and socially.

Lothspeich, who currently studies education and teaching at the University of Illinois, noted that some of the most important components to improving the gifted programs are the teachers themselves.

“The gifted program can be a really positive experience…as long as the kids aren’t presented with teachers who intimidate them or make them feel inadequate,” she stated, indicating that her current studies in education have developed her perception of the gifted program today. “So much of the classroom experience depends on the environment that the teacher creates.”

It is important to note that the separated gifted program at Adler Park School is no longer an established program today. Today, students who choose to study in District 70’s gifted program only do so at their local elementary school, as opposed to traveling to Adler. Essentially, this means the students are now pulled out of their classes throughout the week to study in the separated gifted courses at their respective elementary schools. The LHS Class of 2020 was the final class that was offered the transfer to Adler’s gifted program.

In the District 70’s gifted programs, students have the opportunity to work hard and strengthen their academics — with activities like constellation projections in a space-stimulated dome and lessons centered around complex polynomials. However, staff members and students both emphasized that “gifted” does not mean better than others.

The “gifted” children complete the rigorous tests of academic growth; and when reflecting on their experiences, the students made it clear that while the pressure to excel beyond the gifted expectation is extremely burdening, their opportunities were extraordinary, and in some cases, unique gifts in themselves.