Navigating the n-word

**Note: We are choosing to leave the n-word uncensored in some areas throughout the article as an effort to thoroughly explore the word’s connotation, and we find it beneficial to explicitly say the word instead of masking it.

Etymology of the n-word

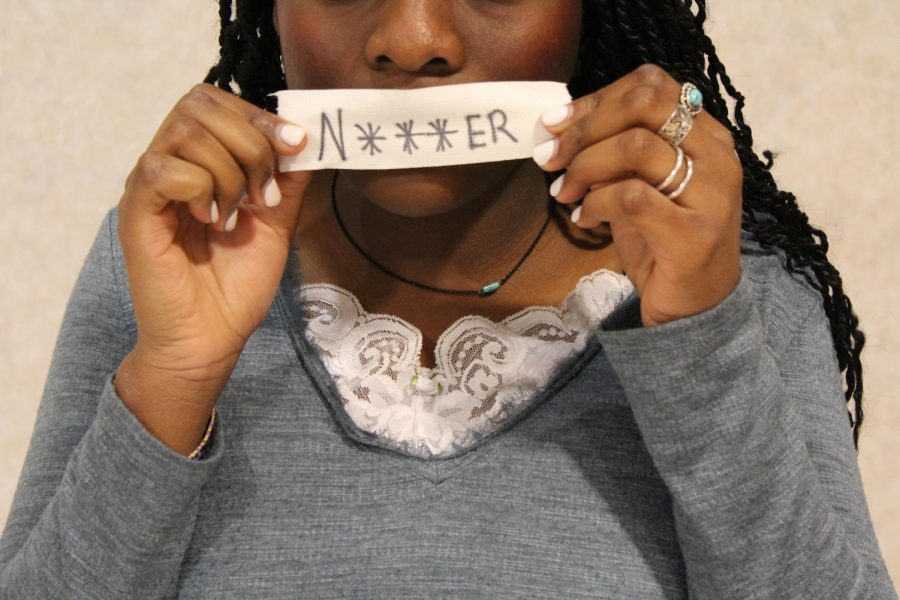

The n-word is one of the most divisive words in American history. The simple utterance of this six-letter word can bring about a whirlwind of painful emotions to many blacks in America.

It all began in the early nineteenth century in the United States, when people started to first use the word “nigger.” According to the Public Broadcasting Service, in the era of enslavement, the words “nigger” or “black” were inserted in front of common American first names to distinguish a black slave from a local white person. The usage of the word today still remains ambiguous to some, as it can be used politically, derogatively or among the black culture affectionately. However, the epithet is considered an abusive slur when used by white people. In recent years, the word has since gained more acceptance in youth culture through song lyrics and stand-up comedy, PBS reported.

According to National Public Radio, nowadays “nigger” and “nigga” are used among blacks to reclaim the pain that is associated with the word. Blacks recruited the word partly as a reclamation and partly out of an inferiority complex rooted in oppression. For some, NPR said, the word has evolved into a term of teasing affection, while other blacks do not view the word in such a positive light.

The complexity of the n-word is an issue that plagues the whole U.S., and our intention is not to clear up the usage — as that would be an almost impossible feat — but rather to explore the usage of the word in a town like Libertyville.

The usage of the N-word in music

In today’s society, the words “nigger” or “nigga” are often used in hip-hop music by black artists to reclaim the word, and some white people find it acceptable for them to sing along to it in music as well.

However, it is a hazy line. The popular Netflix show “Dear White People” depicts the blurred line of the usage of the n-word in black music in an episode at a party scene.

The beginning of the scene includes black and white college students who attend a frat party. The vibe is chill and everyone is dancing and having a good time, until a white friend named Addison drops the n-bomb while singing along to a hip-hop song. A black character named Reggie asks Addison not to say it anymore. Addison explains that he doesn’t “really” use that word, but that he’s just “singing” along.

This is where the debate begins. If someone chooses to use the n-word to sing along in music, is it then acceptable for anyone to say it, or should any usage of it be banned?

Senior Eddie Moy, who is a member of the club Scone Thugs and Harmony, which listens to and discusses hip-hop music, believes that “it is okay [for anyone to use in music] because it is just expressing art. I think it is okay to say it in general because language is what you make of it. It’s just a word. I think it is really what you have as your meaning for the word.”

While Moy believes that the word should not be given power, AP Psychology teacher and avid hip-hop listener Mr. Jonathan Kim upholds the belief that the word inherently has power ingrained in it and one cannot choose to not give it power.

“The ability to say that the word only has meaning if you give it strength or power is a representation of white privilege. For the black community, that word is naturally charged, and there is no way for it to not have meaning or power,” Mr. Kim explained. “Whether it is in song lyrics or in everyday conversation, or joking around, whatever — it is not okay for anyone that is not black to just choose to say it.”

What about without the hard “r” — does that change the meaning?

Having come a long way from using the term “nigger” as a derogatory term to distinguish black slaves from a local white person, the word has since been adapted as a response to cultural changes as time has passed. Passed down from the word of mouth, the term has multiple connotations depending on the way it is pronounced and in the context in which it is said.

In the late ‘90s to early 2000s, Ms. Sharra Powell, an English teacher who is African-American, explained that there was a movement for “some individuals in the African-American community, [primarily] the hip-hop community, to use the term ‘n-i-g-g-a’ instead of ‘n-i-g-g-e-r’, [with] ‘n-i-g-g-a’ being a term that wasn’t hate-filled. There was this idea of taking the hate out of the word.”

Pronouncing it without a hard “r” at the end is now referenced by some as a similar term relating to “buddy” or “friend.” Given that the word is historically ingrained with negativity, there are an array of opinions as to whether this is still offensive in use.

Junior Liam Ness, another member of Scone Thugs and Harmony, expressed that he thinks “it’s what you make of it. If you are using it to say brother or friend, then it is fine, but if you are giving it that hate that’s in the history, then it’s not okay.”

There is still an ongoing debate about whether it is alright to call somebody “nigga.” Contrary to Ness, some, including Ms. Powell, feel no matter the intent behind the usage, there is still a history tied to the word that spelling cannot change.

“There’s too much negativity behind it,” explained Ms. Powell. “It’s a derogatory term, so I wouldn’t call my friend a derogatory term.”

Black people saying it to black people — is it a double standard?

As Chance the Rapper rapped on the popular track “Famous” by Kanye West, “And don’t say nigga unless of course you black nigga.” Mr. Kim upholds some of the same sentiments that Chance the Rapper sang about: “If the black community chooses to use it, then that is okay.”

However, Mr. Kim believes that people who aren’t black are held to a different standard. “If I’m going to make any black individual uncomfortable, then I don’t need to use it. The word is not necessary. I’m going to cut it out of my vocabulary,” Mr. Kim said.

Senior Kharisma Strawder, who is African-American, has a different view of the usage of the n-word and believes that no one should be able to say the word, regardless of their race.

“My grandma is from down south and wasn’t living during slavery, but she was living through the repercussions. So she doesn’t tolerate [the usage of the n-word], so I’ve never been one to say it, and I just don’t feel comfortable saying it,” she said. “I don’t think anyone should say it, whether they are black or white or whatever, especially people who aren’t black because it is degrading. For people who are black, it is degrading to yourself, so you shouldn’t say it.”

However, for some blacks, “nigger” or ”nigga” are not degrading, but rather a way to empower themselves with a word that was historically used to make blacks feel inferior.

For junior Davion Thompson, who is partially African-American, it gives him “a chance to express myself since I’m mixed black and white. It is one of those things that helps me show a little bit of heritage from my black side of the family, since I grew up in Libertyville and this town is more of a whiter town than others around.”

The n-word at LHS

There is still a continuing debate on whether it is all right to use the n-word, and if so, who can say it and in what context. Libertyville has a low presence of racial diversity, which may play a role in how people react to using and hearing the word.

The usage of the word has increased over the past few years at LHS, whether it is meant in a derogatory or friendly manner. It has been observed and heard by students and staff members in a variety of locations, including the hallways, classes and locker rooms. Ms. Powell reflected on a situation that happened a few years ago where a song came on in the boys locker room that included the word “nigger” a multitude of times. A white boy was rapping along with the song saying every word, and a “black student who was in there got very angry, and an actual physical altercation ensued because of it,” she said.

Added Thompson: “It’s been progressing a whole lot; lots more people are saying it, I’ve heard.”

Overall, there is a community of blacks much bigger than what is seen in Libertyville. No individual black person can be singled out to be the spokesperson for their ethnicity. What may be right to one can be wrong to another. Ms. Powell explains this concept to her students by saying that “there’s not really a black people meeting. It’s not like me, Oprah and LeBron all sitting next to each other, all saying ‘Hey, how do we feel about this?’”

Leaving Libertyville can open a new world full of different experiences, cultures and beliefs. How community members embrace the word here may not necessarily accurately reflect how it is viewed in other parts of the country or around the world. History teacher Ms. Sarah Greenswag asserted that “it would be beneficial for our kids to get a better sense of how other people experience this world because we do have a very, very narrow, small-world view here, where we can make a lot of assumptions.”

While the n-word is rooted deep in American history, the meaning is continuously changing for some and it can be hard to comprehend the true complexities of a two-syllable, six-letter word. However, regardless of the interpretation of the word, one concept that Thompson expressed remains constant: “This particular word is powerful for every black man and woman everywhere.”